Jacques LeBlanc is a man with a mission: fossil hunting. A French-speaking Canadian from Quebec, he started collecting fossils when he moved to Calgary in Western Canada to embark on a career as a petroleum geologist. Since then his hobby has taken him all over the world – hunting for whales in the Atacama Desert was one of his expeditions – and he arrived in Qatar to work as a geologist in 2007.

The Qatar desert may be a tad short on whales, but there’s plenty of ancient marine life here to fascinate both geologists and amateur enthusiasts alike. The Qatari peninsula lay under the sea more than once, and Jacques eagerly studies the remains of creatures ranging from crocodiles to crabs which flourished here many millions of years ago and lie scattered on the surface of what is now a dry desert land, or embedded in its rocks.

Over the past few years, Jacques has done much to interest and inform the general public about the fascinating geology of Qatar, and not least through his website.

There are fossil-hunters who closely guard their sites like mushroom hunters who have discovered a promising area for their favourite delicacies, but not Jacques. It didn’t take him long after his arrival in Qatar to realise that the country had no readily available publications on its surface geology. He set out to correct this void by writing two informative and illustrated guides, one on the general geology and fossil content, and the second about the rich Miocene deposits of the Dam Formation in south-western Qatar. These he placed online on his website, for anyone interested to download.

Acknowledged to be the leading authority on fossils in this area, he also gives presentations on his subject and leads expeditions for the Qatar Geological Society and other organisations to view fossil-rich sites. On a warm spring day in February, he led a field trip for the Qatar Natural History Group [QNHG] to an area of south-west Qatar with Miocene features from what geologists term the Dam Formation, dating to some 18 to 22 million years ago. It was literally a walk through time, to sites separated by many millions of years but by only a few metres on the surface. Besides fossils from all periods the group was shown an ancient sand dune, now sited on an upland well inshore, and colourful river pebbles of basalt and quartz that had travelled a thousand kilometres or more from their place of origin.

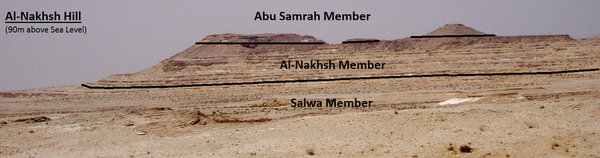

At Jebel Al-Nakhsh, a prominent hill that rises to a height of 90 metres beside the Salwa Road a few kilometres before the Salwa/Abu Samrah border, Jacques explained that its narrow horizontal and clearly defined stratas, known to geologists as ‘members’, illustrate three periods of time within the Miocene: the Salwa, Al Nakhsh and Abu Samrah Members, with the oldest (Salwa) layer at the bottom. On the lower slopes of the hill lies a lithified dune, from the Al Nakhsh Member, composed of the red, iron-stained sand more commonly found in the UAE, in vivid contrast to the pale golden sand surrounding it. Its complex tilted layers were the result of changing directions in wind and waves, now compressed into siltstone, a finer version of sandstone.

A short distance away the geology dramatically changes, to a low ridge of grey, crumbling limestone where vaguely shaped flattened mounds and circular depressions appear. These are the remains of stromatolites, the oldest living forms of life on earth, known to have been in existence 3.5 billion years ago. Slow-growing single-celled microbes [cyanobacteria] form colonies and trap sediment, which reacts in water to form limestone. Because cyanobacteria are plants they photosynthesise their energy from the sun. ‘A by-product of this photosynthesis is oxygen,’ explains Jacques,’ so stromatolites can be regarded as the source of all life on earth. These organisms, when living, existed in very shallow water with high saline levels, where the gastropods that would have fed on them couldn’t reach them.’ It can take a stromatolite a hundred years to grow 5 cm, so the fossilised circular shapes on the ridge, some of which had a diameter of over a metre, must have been living for thousands of years.

For many years stromatolites were known only from fossils, but then in the 1950s a thriving colony was discovered in Shark Bay, Australia. Now they are known in several places in the world, including Qatar, where stretches of stromatolites, looking rather like layers of soft, greyish, gently bubbling silt, survive today in the Umm Tais reserve in north Qatar, and south of Al Wakra on the east coast.

Also on Jebel Al-Nakhsh, and still in the Al Nakhsh Member, are expansive outcrops of glittering gypsum pavement, with glassy crystals up to a metre long. ‘The only other place on earth where such pavements are found is a site in Sicily,’ comments Jacques. It is astonishing that the peninsula of Qatar, although small, contains so many geological rarities: gypsum pavements, living stromatolites and of course the phenomenon of the eerie ‘singing dunes’ so popular with visitors but found in only thirty places world-wide.

On top of the ridge leading to the summit of Jebel Al-Nakhsh and above the Abu Samrah Member are scatters of smooth, coloured pebbles, shaped and polished into pyramidal forms by the wind. These ventifacts, which date to the Hofuf formation, are known to geologists by their German name of dreikanters (‘three corners’). Rolled by the wind over thousands of years, they gradually assumed a three-faceted shape.

From then on for the group of visitors it was downhill all the way, to visit an extraordinary area where a flat limestone surface showing in places above the drifting sand is covered in thousands upon thousands of tiny, white circular shapes: echinoderms or sea urchins. The size of shirt buttons, these now extinct miniature animals died and were gradually formed into fossils. Finally Jacques LeBlanc showed the group one of his special discoveries: the remains of a dugong which died even longer ago than the echinoderms, in the oldest ‘layer’ of the Jebel Al-Nakhsh area, the Salwa Member.

Now its ribs lie weathered and crumbling on the surface, embedded in rock. Reconstructing the death scene like a detective, his guess is that the marine mammal was attacked and killed out at sea by sharks and that its disintegrating body gradually drifted onto the shore, to rot and be covered by sediments. Having populated the seas of Arabia many millions of years ago, dugongs still live and breed today in the area between the north-west coast of Qatar and the nearby Hawar island archipelago [Bahrain] although their numbers are badly depleted by former hunting and the present dangers of boat strikes and entanglement in fishing nets. Only with determined conservation efforts by government organisations will these gentle, slow-moving creatures, which have lived in this region for so many millions of years, survive into the next century.

For more Information, visit Qatar Natural History Group’s website and Qatar Geological Society’s website.

Author: Frances Gillespie

For more information on Frances Gillespie, read Marhaba’s post Chapters of Life.

Copyright © Marhaba Information Guide. Reproduction of material from Marhaba Information Guide’s book or website without written permission is strictly prohibited. Using Marhaba Information Guide’s material without authorisation constitutes as plagiarism as well as copyright infringement.